Travel

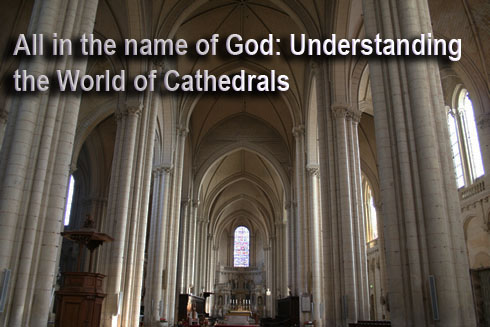

Understanding the world of cathedrals: getting to know the workers and their work

But who were these dedicated workers? First, there was the architect or maître d’oeuvre (French term utilized until the word architect was used, meaning master of works).

About the architect or maître d’oeuvre

He was an excellent communicator, who supervised the work of the many skilled workers. He was the most important man at the building site. French contemporary historian François Icher says: ”Man of knowledge, the architect is equally a man of power.” Most of the time he had started his career as a stonecutter or a mason. He was forbidden to work on many sites at a time. It was a rule he had to follow to make sure he was always available for that cathedral. Architects didn’t all have the same type of contracts: some for one year period, some were available for their entire life and some just until the project was completed.

Copyright Markus Leupold-Löwenthal, Fenstergucker, Vienna Stephansdom

Labyrinths

While most architects until the beginning of the 13th century remained unknown, it was sometimes possible to read their names, carved in the stone, in a drawn labyrinth.

The labyrinth in the Middle Ages was an important symbol for the pilgrims, who could not go to the Holy Land. Praying in a certain way made them feel closer to God. Some architects, during that time, in remembrance to the architect, Daedalus, in the Greek mythology, left their name in the stones of the labyrinth. This was a sort of memorial linking them to the first architect.

In order to be called an architect, the worker had to have had proper training at school, which did not exist in the Middle Ages. Most of them were master masons. Nevertheless more and more architects were being recognized for their knowledge and work and had more power.

Labyrinth at the Notre Dame Cathedral in Poitiers, France

The other workers

There were too many workers to cite them all, but the major ones were: freemasons, stonecutters, carpenters, blacksmiths and glassmakers. Most had been trained with the architect or had once worked with him before. The blacksmith, responsible for making nails and iron tools, was always needed on the site. The quarry man extracted the stones. His hard work was poorly paid but very important at the beginning because he prepared the stones ready for the foundation of the cathedral.

Each trade was passed from father to son like glassmakers. The glassmaker drew, colored and assembled his pieces with lead. It was a slow and difficult work. Most names remained unknown today. The carpenter was responsible for the scaffoldings and for making all wooden tools for the framing of the cathedral. Without his work, the roof could not have been able to hold up. He invented useful machines such as a hoist.

The roofer had to make sure the roof was watertight and was in charge for emptying the gutters and covering up the framing vaults with leaves of lead.

exhibit at Notre Dame of Paris cathedral

Work days and lodges

Work was hard and long, from sunrise to sunset. Men had Sunday off in France, but in England they were also off on Saturday afternoon. Workers in England had two additional daily breaks on top of their hour lunch break.

Lodges were built for the Compagnons and were used for relaxation, work and seeking protection against bad weather. The Compagnons (word comes from the French, meaning friend) were a group of traveling craftsmen of the same trade.

Sculptors, stonecutters and glassmakers also worked in the lodges often, especially during the winter season.

Travel

Traveling from city to city, where work was available, was very common because of the frequent stops of the construction. Once they heard about an opportunity, the workers would often leave together as a team with an architect.

While some experts believe that many town people regularly worked at no cos, pushing a heavy cart for example, other believe it is a myth which has been exaggerated. Most, who helped, were paid workers with a different salary in the winter and in the spring. Winter work was much more difficult and therefore was better renumerated.

Builders of a medieval age cathedral – exhibit in Notre Dame of Paris

Payment

They were paid by the task or by the day, which explains why today one still can see the marks the stonecutters and freemasons left behind.

Marks were left by the workers to keep track of their work and facilitate payment. The architect was paid by the year with bonuses and received clothing in addition.

re: Poitiers Cathedral. I would like to know where the wall drawing of the labyrinth came from please. I am illustrating a book on labyrinths and this is a good image to include.