Career & Entrepreneurship

Chapter 4: Debunking Jargon – Asset Classes – Investing made easy by Rosa Sangiorgio

Investing made easy is a bi-weekly series by Rosa Sangiorgio exclusively for Vivamost

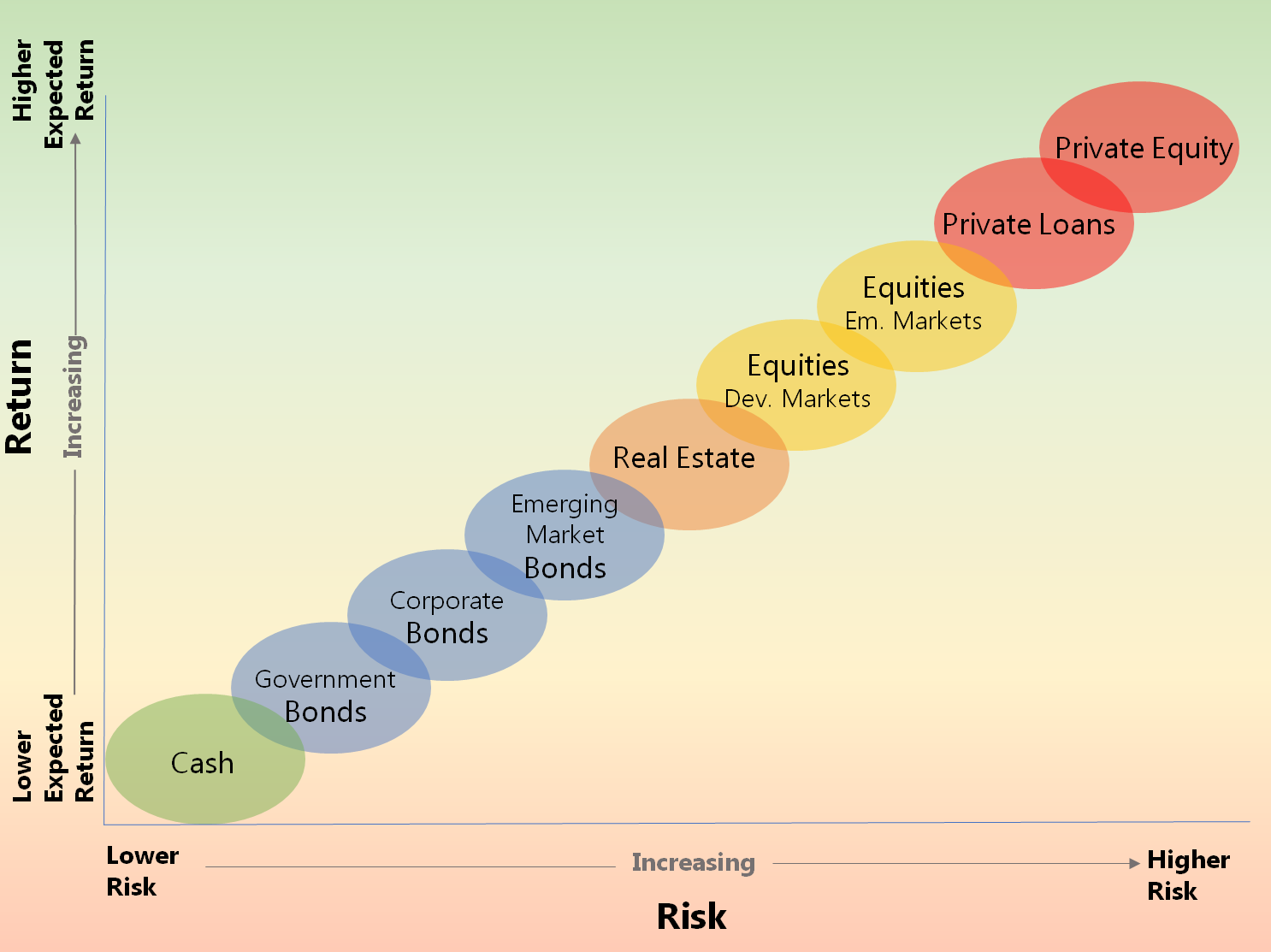

In the past weeks during our journey through investments, you’ve identified your needs. Now it’s time, in the next few articles, to have a look at which investment opportunities are out there, and how you can pick those aligned to your identified needs (by looking at their risk, expected return, time horizon and values).

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

As investors, we group investments having similar financial characteristics in so-called asset classes. You‘ll learn that the right portfolio for you will include your own mix of those asset classes (the so-called asset allocation), but first things first, let’s explore the characteristics of these main asset classes.

In this and next article we will explore the following asset classes:

- Cash

- Fixed Income

- Equity

- Real Estate (next article)

- Private Equity and Loans (next article)

- Other Asset Classes (next article)

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

Cash

The simplicity and familiarity of cash is one of its biggest advantages. Cash and cash equivalents (i.e. savings deposits, certificates of deposit) offer the lowest return, but at the same time are the safest investments. The chances of losing money held in cash are generally extremely low.

![]()

Good

- No capital loss

- Nothing is more liquid than cash! If you lose your job and need money, your cash reserves can quickly satisfy whatever you need

![]() Bad

Bad

- Cash purchasing power will be hit by inflation over time. CHF100 in 2016 is only worth CHF98 of goods today.

Photo by Sandy Millar on Unsplash

Fixed Income (or Bonds)

Bonds are “I owe you” securities issued by an entity such as a company or government. When you buy a bond, you’re effectively lending money to the so-called “bond issuer”. In exchange for your money, the bond issuer pays you a stream of interest (i.e. coupons), during the life of the bond, and at the end of the bonds’ lifetime, (i.e. at maturity) returns you the original money invested.

Depending on who issues the bond, the repayment of your investment, the periodical interest, or both, are more or less at risk. Countries are less likely to go bankrupt that companies, but it still happens occasionally that a government will default, recent notable examples are Venezuela, Greece & Argentina. Paying attention to the ratings of bond issuers is therefore worthwhile.

Imagine you lend money to your friend Lisa who wants to start her own business. She writes you a debt note promising that she’ll give you back that 1’000 CHF plus 5% interest per year in 3 years time. One year later, you need money but Lisa is not yet ready to repay. You decide to sell her note to Paul, at a price you both deem fair, taking into consideration Lisa’s history in repaying debts, her reputation and how her business is performing (i.e. her rating). That’s how bonds work.

Securities issued by governments and corporations are usually “listed” in exchanges, therefore investors can buy/sell them without having to “negotiate” with the issuer. Such securities are usually called “bonds”. Non-listed debt securities (i.e. Private Loans) – like your loan to Lisa – are in a dedicated asset class due to their less “liquid” and more “risky” characteristics.

The more risky the issuer and longer the duration, the higher the price volatility and consequently the risk of loss when selling before maturity. You can match the maturity date of your bonds to your desired investment time horizon and thus know exactly what your return will be if you hold the bond until maturity (i.e. yield to maturity).

To check values and impact, it’s important to analyze both the issuer and the use of proceeds (what the issuer is doing with the money collected through the bond). A special type of bond is available called “Sustainable Bonds” (e.g. Green or Social Bonds). Such securities declare how the proceeds will be used and guarantee high transparency. We will dedicate a full chapter to those bonds.

![]()

Good

- Historically, they’ve provided a better return than cash.

- Usually, a low correlation with equities makes government bonds a useful way to protect a portfolio from the stock market crisis.

![]() Bad

Bad

- Bond returns are historically lower than equities.

- They are vulnerable to inflation (unless you choose index-linked) and changes in interest rates.

Photo by Alice Pasqual on Unsplash

Equities

When buying equities, you buy a share of a company. As such, equities have the potential to produce returns in two ways: through increases in share price, and/or in the form of dividends. Neither of these is guaranteed and there is always the risk that the share price will fall below the level at which you invested, and/or the company doesn’t pay dividends.

Let’s assume that Lisa has a business idea, and needs more money than she has available to realize it. You like her idea and decide to participate in her business, Lisa invests CHF 9’000 in her business and you invest CHF 1’000. The overall capital is, therefore, 10’000 and you become a shareholder with 10% equity in Lisa’s business.

When companies reach a certain size and/or want to be sure that their shares can circulate freely, they list their shares on a stock exchange. These are usually called “public” equities, to distinguish them from the non-listed Private Equity (i.e. Lisa’s business). We’ll dedicate space to Private Equity in the next chapter, as investing in Private Equity is quite different to exchange-listed equities.

Equities are historically the riskiest and best rewarded of the main asset classes.

From a time horizon perspective, the longer you can hold the better. Five years being the bare minimum, 10 years being a more comfortable term.

To understand the values and impact of a company, it’s key to review the internal business model, including the culture and vision. Also important are the sector in which the company operates, its core products and last but by no means least, the company’s effects on society and the environment.

![]()

Good

- Equities have traditionally performed better than other asset classes when it comes to long-term returns.

- Equities are capable of beating inflation.

![]() Bad

Bad

- Severe losses can occur at any time and frequently do.

The Cathedrals of Wall Street by Florine Stettheimer

We’ll explore Real Estate, Private Equity/Loans, and other Alternative Asset Classes in the next Chapter, until then, stay safe and healthy!

Did you enjoy this chapter? Don’t miss out on the future ones in this series. Subscribe to our upcoming articles here.

Additional Reading:

Asset return expectations and uncertainty

2020 Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions

About the Author:

Rosa Sangiorgio

Rosa Sangiorgio, an Independent Advisor, is an expert at scaling investment methods that generate positive, socially responsible and environmental welfare impact in addition to a financial return. She worked for several European Financial institutions in the area of Wealth Management and Private Banking. Also, she was Head of Sustainability and Impact Investing in the Investment Management team of Credit Suisse until January 2020. Rosa is also a CEFA charterholder and TEDx speaker.