Columns

Chapter 6: Are derivatives evil? – Investing made easy by Rosa Sangiorgio

Investing made easy is a bi-weekly series by Rosa Sangiorgio exclusively for Vivamost

During our last chapter on alternative investments, we talked about commodities and hedge funds, you may have noticed that I lightly mentioned financial derivatives. Most probably you had already heard the term whilst reading the news or chatting with friends, for example during the Financial Crisis of 2008. If you felt lonely in during those conversations, because you weren’t really sure what derivatives are, then this article is for you.

Licensed by Rosa Sangiorgio from www.CartoonStock.com

Credible promises

Financial derivatives were originally created to hedge risks, nowadays they are also used for speculation. The first derivative contracts were written in cuneiform script on clay tablets in Mesopotamia (luckily for financial historians, extremely durable!). These derivatives were contracts for the future delivery of goods. One of the first known examples, probably from 19th century BC, is “a tablet in which a supplier of wood, whose name was Akshak-shemi, promised to deliver 30 wooden [planks?] to a client, called Damqanum, at a future date.” (cit. Van de Mieroop, 2005).

Derivatives continued to be used by the Greeks, the Romans and the Byzantines. During the Renaissance, financial markets became more sophisticated in Italy and the Pays Bas, derivative trading on securities spread from Amsterdam to England and France at the end of the seventeenth century, and then from France to Germany in the early nineteenth century.

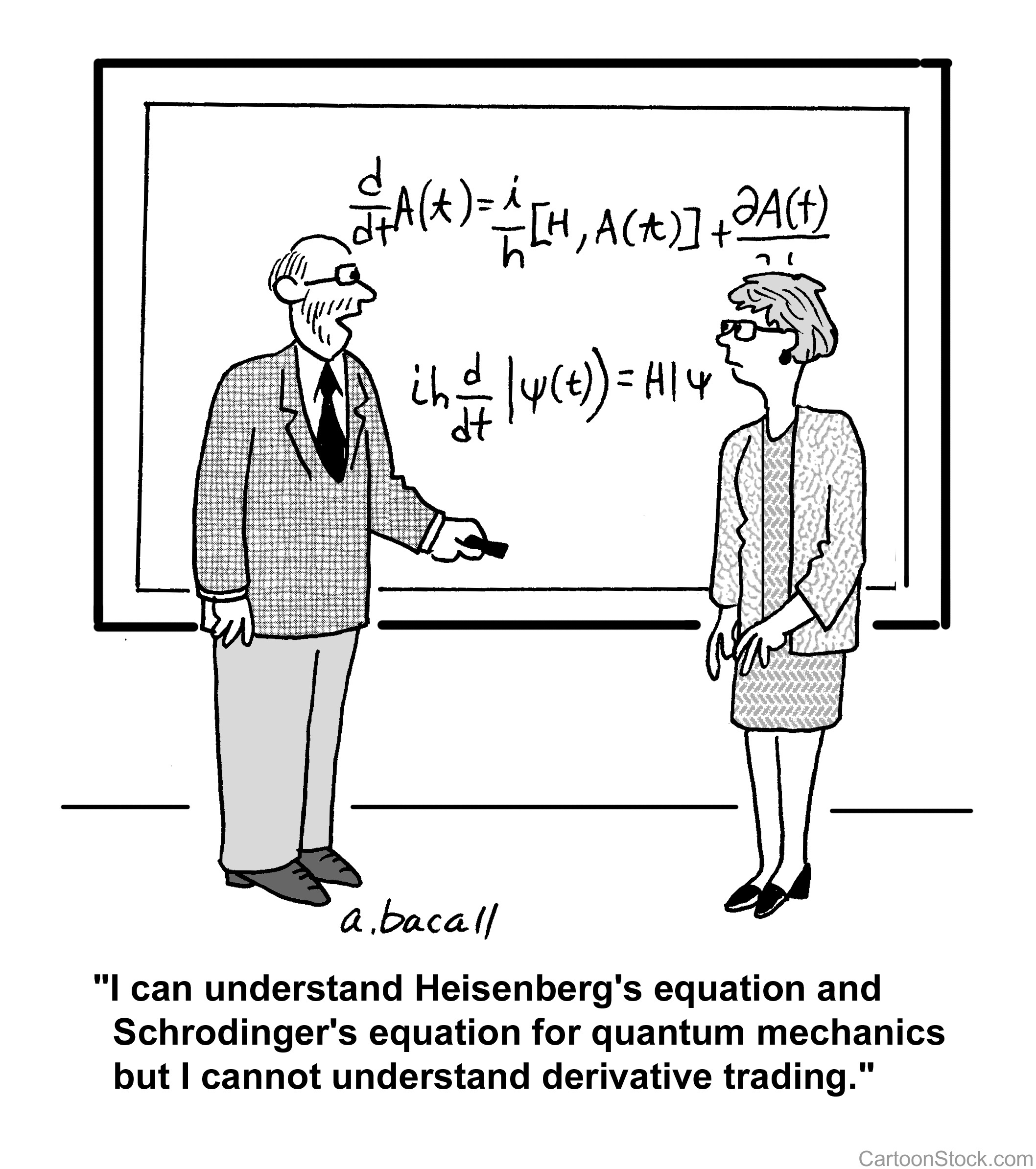

Source: www.indiabullssecurities.com

As probably happened with Akshak-shemi and Damqanum, derivatives were born as contracts between buyers and sellers to provide a sort of “insurance”. The lumberjack would enter a future contract with the carpenter to block a price for the wooden planks to reduce the risk of price fluctuation.

For example, on July 1st the lumberjack Akshak-shemi would enter a futures contract with the carpenter Damqanum to sell him 30 wooden planks at 100 CHF on September 30th. Once having signed the contract, both parties could then ignore any movement of the market price of wooden planks, as the transaction will in any case be executed at 100 CHF on September 30th. Futures contract helped both buyers and sellers to plan.

Are derivatives that complicated to understand?

Financial derivatives are contracts between two parties that specify conditions under which payments are and will be made between the same two parties. All derivatives are “derived” from underlying assets such as stocks, commodities, or even measurable events such as weather. Despite this commonality, derivatives have many different forms including futures, forwards, warrants, swaps, options. The variety across all these types of contracts and underlying is part of the reason why many find them hard to understand.

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

Speculation versus hedging

Derivatives were born as a hedging tool, but soon became a good tool to speculate.

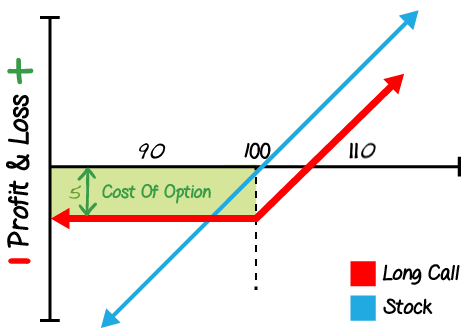

For example, a call option offers the buyer the opportunity to buy the underlying asset at a future date at a defined price. Unlike futures, the holder is not required to buy or sell the asset if they choose not to (hence it being called an option).

As a quick example of how call options work.

It’s July 1st and IBM stock is currently trading at 100 USD per share. If you believe that IBM’s price will rise, you can either directly buy the stock, or use derivatives.

Direct purchase of the IBM share

July 1st: You buy 1 IBM Stock at 100 USD.

December 1st:

- If IBM price has risen to 110, you gain 10 USD (10% profit on investment)

- If IBM price has dropped to 90, you lose 10 USD (10% loss on investment)

Purchase of a Call Option on IBM

July 1st: You buy a call option on IBM. It costs 5 USD and gives you the right to buy 1 share of IBM at 100 USD on December 1st.

December 1st:

- If IBM price has risen to 110, you exercise the option, purchase the share at 100, and immediately sell for 110. You gain 10 USD from the trade, minus the 5 USD that you paid for the option, you gain 5 USD (100% profit on investment – invested 5 USD, gained 5 USD)

- If IBM price has dropped to 90, you have no interest in exercising the option, and let it expire, therefore only losing the price of the option that you had paid in advance (100% loss on investment – invested 5 USD, lost 5 USD)

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

In this example:

- the option has allowed you to participate to the upside, but limited the downside to the cost of the option you have paid.

- looking at the % return on investment, you see the leverage effect created by the fact that with the option you only pay the option price and not the full price of the underlying.

Options (and derivatives in general) are powerful because they can enhance an individual’s portfolio. They do this through added income, protection, and even leverage.

(all numbers above are examples and not linked to real market prices or margins)

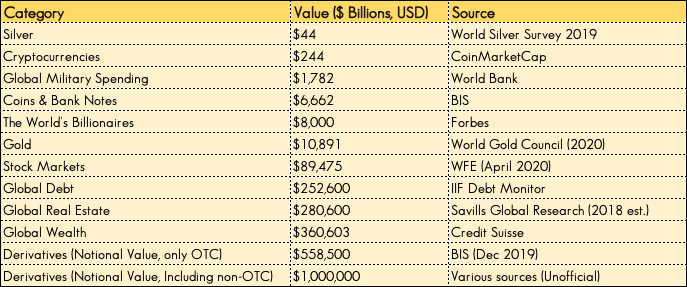

Huge market

According to the most recent data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the total notional amount outstanding for contracts in the derivatives market is estimated between 500 Trillion and 1 quadrillion, depending on whether or not we consider only the traded contracts, or also the unregistered ones. It’s a huge number, if total wealth is estimated at 360 Trillion.

Source: www.visualcapitalist.com

Are derivatives inherently evil?

While quite useful in some scenarios, not everyone is a fan of using derivatives, including investors as experienced as Warren Buffett who once described derivatives as “financial weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal.” I personally believe that derivatives aren’t inherently bad, but they become dangerous in case of overexposure and uninformed investors. Derivatives are probably not to be used by the average investor on their own, but they can add value when used appropriately and in moderation. Regardless, it’s useful to understand them, and know their risks and benefits.

Photo by Kovah on Unsplash

About the Author:

Rosa Sangiorgio, an Independent Advisor, is an expert at scaling investment methods that generate positive, socially responsible and environmental welfare impact in addition to a financial return. She worked for several European Financial institutions in the area of Wealth Management and Private Banking. Also, she was Head of Sustainability and Impact Investing in the Investment Management team of Credit Suisse until January 2020. Rosa is also a CEFA charterholder and TEDx speaker.