Columns

Chapter 9: Finding the Right Asset Allocation for You – Investing made easy by Rosa Sangiorgio

Investing made easy is a bi-weekly series by Rosa Sangiorgio exclusively for Vivamost

The Critical Asset Allocation Decision

Your long-term asset allocation is one of the most critical decisions you’ll make as an investor. It’s even more important than the individual investments you buy. It accounts for 88% of your investment experience, according to Vanguard research and 90% of your portfolio volatility, according to the famous study of 1986 (see chapter 8). In simple terms, if you’ve invested in a diversified portfolio across a few asset classes, your investment returns will be similar to those of another investor with a similar asset allocation. In the long term, it doesn’t really matter which individual investments you choose.

Given how important it is, you want to get your asset allocation right! So, in this chapter, we’ll briefly look at the theory – so that you don’t get fooled by any jargon – and then we’ll look at how practically this translates to everyday life.

The theory

Similarly to what happens when you do your vegetable shopping, the right asset allocation for you, matches a) what’s available in the market and b) your requirements.

Photo by Katie Jowett on Unsplash

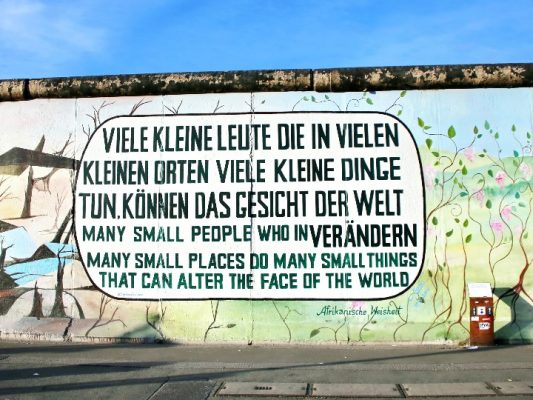

What’s available on the market, is usually called by Financial advisors (and modern portfolio theory) the “efficient frontier”. It consists of the most efficient portfolios with the highest expected return for a given level of risk, considering the actual market situation. Any portfolio lying below the efficient frontier has either a lower return (for the same risk) or higher risk (for the same return) of a portfolio on the frontier.

Your requirements are represented by the so-called “indifference curve”, as it represents the infinite combination of risk and return to which you would be indifferent, it represents the risk/reward trade-off that you are willing to take. The portfolio where the “indifference curve” touches the “efficient frontier” is the right portfolio, considering both the market conditions and your own risk profile.

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

The practice

To build the efficient frontier, we need to make a series of hypotheses about the risk/return of all the existing investment opportunities (so-called “capital market assumptions”) and then calculate all the combinations.

Similarly, to build your indifference curve, you need to go through a lengthy process of testing all the combinations of risk/return to understand where you are indifferent.

Photo by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash

Asset Allocation Calculators

Don’t panic, choosing your asset allocation does not need to be a complex, math-intensive process. Your financial advisor would be glad to help you optimize your asset allocation using his/her bank financial planning software and simulation tests.

That said, if you’re confident that you understand your time horizon and risk tolerance, and have a good grasp of the different asset classes, you may feel comfortable with creating your own asset allocation, either using the free software available at your bank, or one of the many free online apps out there.

Here’s a short list:

- Asset allocation: Fix your mix

- Asset Allocation Calculator

- SurePayrol Asset allocation calculator

- How should I allocate my assets?

All these web-based solutions have in the background a defined list of diversified asset allocations (efficient frontier), and let you fill in a questionnaire (indifference curve). Matching the two gives you the appropriate asset allocation.

Short cuts – Rule of Thumb

We modern humans love short-cuts, even in investing! And no, it is not the “Italian in me bias”. Just look at the “lose-weight-fast” or “get-rich-quick” gimmicks! We want to believe there’s an easier way.

Photo by Rowen Smith on Unsplash

A popular short-cut is the idea that you can take 100 (or, more recently to compensate for longer lifespans, 120), subtract your age, and that’s how much you should have in equities (or high-risk asset classes), the rest in bond. You can read that rule of thumb in magazines and blogs…

There are two problems with this rule of thumb:

- Everyone’s thumb has a different size. You and your life are too unique to put you into a generic category based solely on your age. Yes, age matters. It influences massively your time horizon. But time horizon is just one factor that should be considered alongside things like your return expectations, how long you have to reach your goal, your willingness and ability to take risk with investments.

- There’s more to asset allocation than just equities and bonds.

This rule of thumb is too fast and easy a solution for the very serious issue of asset allocation. Anyway, if you’re new to investing, and you’re only investing a small part of your wealth to try it out, finding a comfortable allocation between equities and bonds is a good start. Then, when you become a more skilful investor, you’ll reconsider your risk appetite, return expectations and cash flows, and look beyond the traditional asset classes.

Even when using short cuts, always remember that your asset allocation is driven by three things: your time horizon, your ability and willingness to take risk, and the size of your financial goal. If any of those changes, it may be time to change your asset allocation.

Your time horizon is how long you have to reach your goal.

The further you are from your goal, the more risk you can afford to take to reach that goal, which translates into a higher allocation to equities. Generally speaking, the younger you are, the more time you have to ride out the up and downs of the equity market and allow the power of compounding interest to work to your advantage (considering that equities historically provide higher returns than bonds).

Remember, the link between age and risk only works if the goal you’re saving for is many years in the future. If you’re saving to buy your first home in three years, you shouldn’t keep your savings in equities, as you won’t have time to recover from a market drop, and so a more balanced allocation with greater exposure to bonds is preferable.

Photo by Jessica Lewis on Unsplash

Ability to take risk and willingness to take risk is not the same.

If you are young, you have a long time horizon and regular income, theoretically, you can afford to take the risk. But if you get nausea at the sight of your portfolio’s value dropping and want to sell at every downturn, better not take that much risk. It is key to avoid a situation where you panic because the volatility of your portfolio was too high and sell when the market is down, only to miss the subsequent recovery.

If your goal is to buy a CHF 10’000 car in 10 years, you may not need to be fully invested in equities. In fact, if you can save CHF 80 every month for those 10 years, all you’d need is a government bond yielding 2% per year to reach your goal. The point being, there’s no need to risk your savings on anything more aggressive if a conservative investment will do the job.

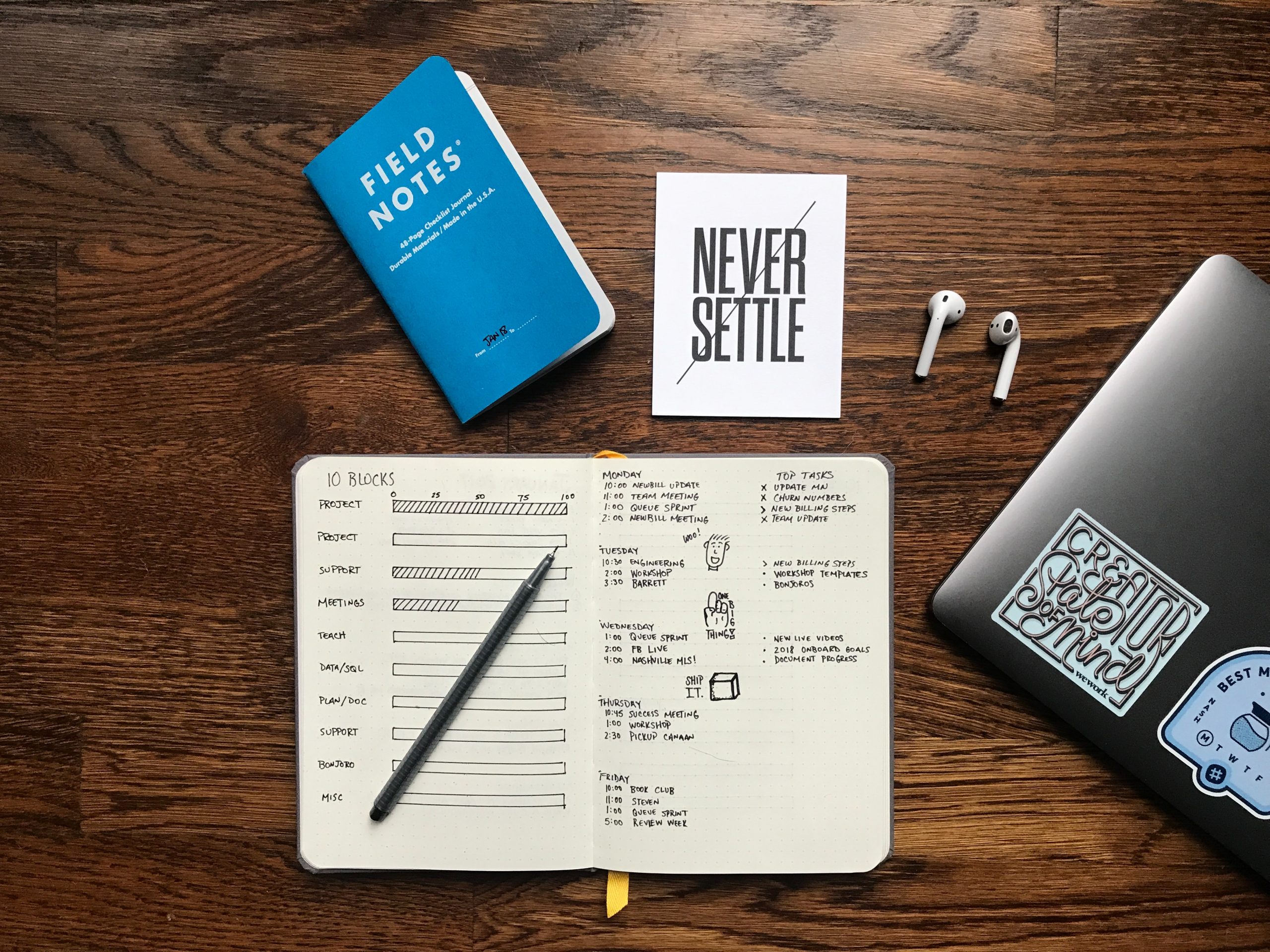

Photo by Matt Ragland on Unsplash

Short cuts – Baby Steps

If you’re only starting investing, and want to practice with a small part of your wealth, you can take a more generalized approach to asset allocation. Perhaps start by determining how long you have to reach your financial goal. If your goal is more than 7 years away, you can generally lean on equities (as in 50% or more), assuming that much volatility won’t give you heart palpitations.

If after a few weeks you find yourself unable to sleep at night because your investments are jumping up and down, then back off your stock exposure. Instead of 50% stocks, try 40%. If you’re still anxious, try 30%. Keep working backwards until you reach a level that lets you sleep at night but stay invested.

Managing your wealth is an art: the art of making the investment decisions that suit your specific investment time horizon. As with any art, it takes time, patience and experience to achieve the optimal result.

About the Author:

Rosa Sangiorgio, an Independent Advisor, is an expert at scaling investment methods that generate positive, socially responsible and environmental welfare impact in addition to a financial return. She worked for several European Financial institutions in the area of Wealth Management and Private Banking. Also, she was Head of Sustainability and Impact Investing in the Investment Management team of Credit Suisse until January 2020. Rosa is also a CEFA charterholder and TEDx speaker.