Travel

Understanding the world of cathedrals: the Cathedral of Canterbury in Kent (England)

Stain glass windows:

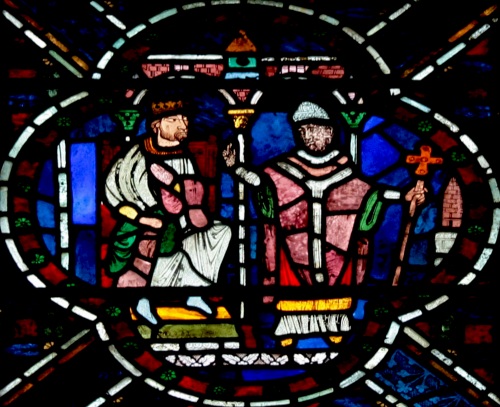

Something that strikes the visitor entering the Cathedral of Canterbury are the beautiful old stain glass windows.

In the Middle Ages stain glass windows were important to churches, a way to get closer to God and to understand better the life of saints, kings, workers and architects. They were also a way to learn about bible stories and the tools used at this time.

Beautiful stain glass window – Copyright: Sacred Destination

A Medieval Historian, Madeline Harrison Caviness spent a decade studying every window of the cathedral during her dissertation from 1967 to 1977. She climbed on scaffolds, reaching places that where inaccessible. A few years later in 1981 she wrote an in-depth 607 pages book “Christ Church Cathedral Canterbury” describing every bit of her research, noting information on the glass shape, measurements, condition, style and iconography. The editor of the book only published about 1000 copies.

She mentions two periods: late Romanesque to early Gothic and late 14th to late 15th centuries. Fortunately many stain glass windows are originally from the Middle Ages from the 12th and 13th centuries. Some windows were restored in the 19th century due to corrosion, vandalism and decay.

For almost 40 years, a conservation glass studio has been caring for the windows. Seven professionals restore and conserve the windows.

One of the largest stain glass windows is the size of a tennis court! Also the oldest stain glass window is called Adam Delving 1176.

In Canterbury are also depicted the miracles of Thomas Becket in the Trinity Chapel. There are 8 Becket windows in total in the North and South Ambulatory.

Monument and effigies:

You may be interested by the many monuments and effigies of kings, priors, archbishops and other important figures, which are found in Canterbury. The earliest monument is from the 13th century.

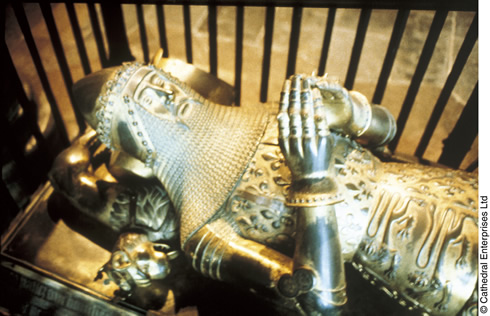

The best known is without a doubt the tomb of Edward of Woodstock known as the Black Prince. Edward became famous for his successes at battles of Crécy and Poitiers. He died in 1376.

His monument made of bronze was decided probably in 1360 in a will before his death. He was the second of the royal family to be buried there, in an outfit like he was leaving for battle. The Black Prince was buried next to Thomas Becket; in fact he would have rather preferred the crypt.

Effigy of the Black Prince, joining hands – Credit: Canterbury Cathedral

Above the Prince tomb on a beam are some of the replicas of what he wore during battle: a shield, a helmet and a coat. The effigy stands between two pillars in the South Arcade. Above it, is a canopy.

Just opposite of the Black Prince in the North Arcade are the tombs of King Henry IV and his wife. The effigies in alabaster are shown hands joining and praying.

Henry IV is portrayed with a costume he wore during coronation. He is buried next to the Trinity Chapel of Thomas Becket due to an oil connection it is said to have existed between the king and Becket.

Unfortunately not much documentation on the monuments is known until 1850. But by luck we have burial registers.

At the end of the 17th century cartouches were used on each memorial to record dates.

Katharine Eustace in her research talks about “sobriety” when describing the monuments at Canterbury. Nothing was really too extravagant. Probably the workers and the masons came from around London.

The monument of William Warham (1503-1532) is the biggest medieval monument in the cathedral. He crowned King Henry VIII and was a friend of Erasmus.

Replicas of the Black Prince shield, coat and gloves

What’s important to remember about the cathedral of Canterbury:

- In late Medieval ages, it was considered a prestigious cathedral.

- It is today one of the best known English cathedrals.

- It has an impressive nave with high vaults and remarkable ceiling designs such as the fan vaults of the Lady Chapel.

- Height of 235 feet (72 m) – Length of 514 feet (1686 m) and West Tower – 130 feet (426 m)

- It has the longest choir in any English churches – 180 feet (590 m).

- The Norman Crypt is the largest crypt in England.

- It is one of the oldest buildings in England.

- It still has the 13th chair of Archibishop St. Augustine.

- The highest leader of the Anglican church sits there.

Three periods, explaining the different styles:

- 1070 to 1089: Norman Gothic style until 1200

- 1175 to 1184

- 1379 to 1503: Perpendicular style until 1530

Crypt – Tim Stubbings – Canterbury City Council’s Tourism Dept

Famous architects, workers and artists who worked there:

- William of Sens: French mason from Sens 1174/5 until 1179/80 – worked on the choir in Canterbury. He fell down and almost died. Known to have worked at the Cathedral of Saint Denis in France. We know about him thanks to the writings of monk Gervase.

- William the Englishman: 1179/80 to 1184 – Finished the work of William of Sens and he worked faster

- Henry Yevele: the master mason of his time (1386-1400). Redid the nave in perpendicular style. Known to have worked on Westminster Abbey, London Bridge, Tower of London and Canterbury city walls

- Richard Beke (1432 to 1458): worked on the central tower. Known for the London Bridge. Was named mason for life in 1434/35

- John Wastell (1490 to 1518): worked at the Abbey Bury St Edmunds. Was considered a modern architect and is responsible for the large fan vaults in Bell Harry Tower.

- Henry Weekes: a 18th century English sculptor, native of Canterbury

- Erwin Bossnyi: Hungarian artist responsible for 4 new windows beginning of 1950

- Patrick Reyntiens: stain glass window artist

�