Family and Kids

Q&A with Dr. Rita Csiszár, sociologist and author of Multilingual Kids

Despite being a linguist, Rita had a hard time with the Swiss dialect

Rita Csiszár moved from Austria to Switzerland because of her husband’s work and she had no idea there was such a difference between the two neighbouring alpine countries.

Just before the coronavirus epidemic, I met Rita in Zurich on a February evening. A Swiss-Hungarian Facebook group arranged a meeting, and my friend Anna, who had already attended such dinners several times, invited me to go with her. A table was reserved for us in the Italian restaurant Santa Lucia near Paradeplatz. The restaurant was soon filled with loud Hungarian chatter. A perfect combination of cheerful conversation and delicious Italian food – what more could one wish for? Rita was sitting right across the table from me, we talked a lot about Swiss integration, the life here, neighbours and of course Rita’s books. I was a little envious of her, of the books that she had already completed and published and that she was able to go through the process from writing to publishing. We agreed right then that I would interview her.

The language development and integration of bi- and trilingual children into new cultures are the main themes of Rita’s books. Her job has also been negatively affected by the coronavirus: she had to cancel all events, pedagogical trainings and personal counselling sessions planned for 2020, whether within or out of the country.

Business card: Rita Csiszár, PhD – linguist, sociologist, language teacher

Current job: Multilingual Kids – founder, author, lecturer, consultant

Publications:

Bilingual and multilingual parenting in everyday life – advice, information, stories. (2014)

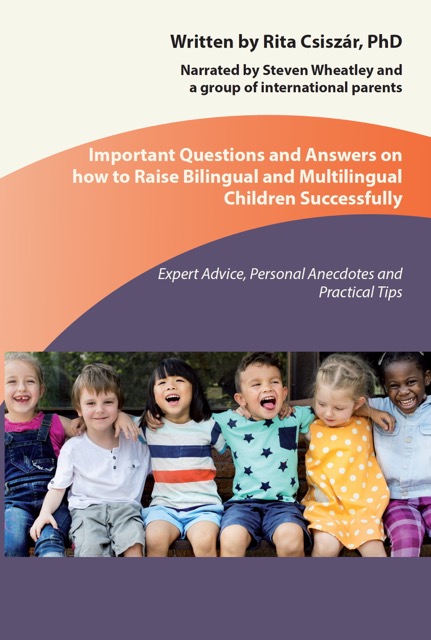

Important Questions and Answers on How to Raise Bilingual and Multilingual Children Successfully – Audiobook and eBook (2019)

Studies: University of Pécs, doctoral dissertation in applied linguistics / Central European University, Sociology / University of Veszprém, high school English teacher

I remembered that in February, the publication of the e-book and audiobook in English was one of her primary concerns, so I started our conversation with this topic.

As far as I know, in the meantime you have managed to publish your new audiobook in English, which also deals with the subject of bilingualism and multilingualism in childhood. What made you write a book on the subject and to even make an audiobook?

RCS: From my many years of experience as a researcher and consultant, I felt the need for a publication that would provide useful knowledge and practical advice to concerned parents. This was the aim of my Hungarian manual published in 2014. The new English-language publication – thanks to the language of the publication and the audio material -, will hopefully be able to help even more families with their language-related questions in their daily lives. An interesting feature is that we recorded the audio material in the studio with a team of international parents, which I think made it even more lifelike and authentic.

Let’s start from the beginning! Please tell me how a young lady, who has a degree in applied linguistics, ends up in Vienna?

RCS: I studied and worked in an international environment during and after university. After my part-time studies abroad in Germany and Canada, I obtained a diploma at the CEU Warsaw Campus as part of a postgraduate course. Even before Hungary joined to the EU, I spent half a year in Brussels as an intern at the EU Commission. After graduating, I worked at the university and then at a diplomatic corp. In the meantime, as a PhD student, I started writing my doctoral dissertation in applied linguistics. During this time, I got a scholarship in Austria. I had to collect a hundred language interviews for my dissertation. One of my interviewees was a widower with three teenage boys who moved from Budapest to Vienna. As it happened, he become my husband a few years later.’

What a fabulous and adventurous story! How did you fit into this radically different role?

RCS: It wasn’t easy to become a stepmother “raising” three teenagers, from a single, careerist woman. Then in 2007, our child, Anna, was born. Interestingly, being abroad not only opened up opportunities for me, but it also set some limits. I found myself facing the problem that there was no lunch at the children’s school. So, every day, I waited for them with a hot meal at lunchtime. This broke my days in half and also made it harder to work. That’s when I first thought about how challenging it must be for many women, just like for me, to reconcile family life and careers.’

Were you able to continue your professional development or did you have to give up active work altogether?

RCS: I was able to continue to a certain extent, because I took part in various research projects, I worked at the university and I also did social work. A well-functioning social network of friends and professional relationships just started forming around me. By the time Anna started attending kindergarten, everything seemed perfect. Exactly at this time came the decision to move to Switzerland because of my husband’s work. Our lives suddenly got reorganized, because we couldn’t go together as a family: the two older boys stayed in Austria, so only four of us moved. The youngest boy started studying straight away at EHL in Lausanne, so only three members of our formerly large family were left, with my husband and our five-year-old daughter.’

How did you find Swiss life? How have you settled in?

RCS: As they say: every beginning is difficult. I must confess that I experienced that first period as a culture shock, even though by then I had lived in quite a few different countries for a longer or shorter period of time. I didn’t expect the two neighbouring Alpine countries to be so different. I see today, that I should have prepared more for this change of countries. I had to rebuild my professional life and my local circle. Our little girl took it badly that she had to part with the family and she had to fit in a radically different kindergarten system.’

Did you understand Swiss German? How different did you find it compared to Viennese German?

RCS: Despite being an applied linguist, I had a very hard time dealing with Swiss German. It took me a few years to understand it, even though I had heard so many German dialects in my life. This was partly due to my almost unconscious resistance to this language. I was also able to personally experience what I had seen in my work every day before: emotions and motivation play a huge role in language learning! It helped a lot that our Swiss neighbour gave me “Schwiizerdütsch” classes on a weekly basis.’

You mentioned earlier that your little daughter was very worn out by the changes. How did they affect her?

RCS: As a result of the move, her secure life also turned upside down. She missed his two brothers who stayed in Vienna and was very opposed to the new preschool order. The role of the kindergarten is fundamentally different in the two countries: while in Vienna it is a place for playing, in Switzerland it is part of the education system, where children are expected to have a high degree of independence. The Vienna kindergarten was very homely, with two kindergarten teachers and two caregivers.

In Switzerland, on the other hand, the atmosphere was somehow „Prussian”, and there was only one kindergarten teacher caring for twenty children. While the older children were solving tasks, the small ones (in the same room) were playing quietly. Discipline, raising hands, writing tests (with an hourglass!) – these were the concepts that characterized kindergarten life. While in Vienna, the children were taken to the theatre, the cinema or on a trip, in the new place they took at most a walk in the nearby forest. Anna also complained at home that she couldn’t hold the kindergarten teacher’s hand, who even seemed to push her away as she approached her. Thanks to the negative changes, my little daughter declared with great determination, “Mom, I will do everything to go back to Vienna,” and she really did everything for it.’

It’s almost like a dramatic movie scene! What exactly did Anna do? How should we imagine her resistance?

RCS: She had different behavioural problems: she opposed the kindergarten teacher in every way she could. She seemed unable and unwilling to fit in. The newly graduated young teacher was not prepared for the situation either. Anna ended up in pre-school (Vorschule), so she started first grade a year late. This time, however, was enough for her to “acclimatize,” to get used to local expectations. I would like to mention that in my counselling work, I often see that such reactions are very common among children going to preschool or school when they change countries because of their parents’ work.’

As you’ve probably heard Rita, here in Switzerland, the two pre-school years before school are actually part of school and compulsory education. Presumably this is why pre-school education is stricter than in Austria or Hungary.

RCS: Yes, that’s for sure. If Anna had not already spent three years in a kindergarten in Vienna, this problem mightt not have arisen at all, as there would have been no basis for comparison.

As a parent, what is your impression of the Swiss school system?

RCS: ‘I could analyse both the pros and cons for a long time, but for now I would rather just mention one point. My observations are that the life of a family woman in Switzerland is mostly determined by the structure of educational institutions. In an average German-Swiss town, the municipal kindergarten only starts from the age of 4. Until then, you either have to stay home with the little one, or you have to individually solve the problem of their supervision at a high price. Paid crèches (which are very expensive) are only found in large cities or in areas inhabited by a large number of expats. In fact, in these areas there are a lot of them. Even the two-year kindergarten provides mostly just morning activities, without meals. The number of classes in primary school is also relatively few, so the children are more at home than away. All of this largely determines women’s employment opportunities. Although this feature of the education system has been a deterrent to me in Switzerland, I must admit that, thanks to this social arrangement, the role of mothers and housewives in the land of Wilhelm Tell is much more valued than in many other European countries. The earlier mentioned characteristics stem from the fact that the traditional role distribution in Switzerland is even stronger than in other parts of Europe: the man is responsible for the money, the woman for the household and the children. I am sure that there will be big changes in this in the future.

Despite all of this, you are not a typical housewife, Rita. In 2014 you published your book (more than 400 pages) on educating multilingual children. Compiling such a meaningful and practical book couldn’t have been easy, even with many years of experience.

RCS: I considered the book primarily as a mission task, the desire to help motivated me when I was writing it. I received numerous questions from concerned parents during my years in Vienna, but at the same time there was no literature on the subject in Hungarian, specifically for non-professionals. At the time, however, I had no idea that professional counselling could be built around the book. I was surprised when I got noticed in Hungary and abroad through the book and started receiving invitations from different countries in Europe.

Where were you invited? For what kind of events?

RCS: Wow, it would be hard to list all the places: Paris, Boston, Basel, Amsterdam, Brussels, Nuremberg, Copenhagen, Vienna and so on. Mainly Hungarian communities invite me to give a presentation, as the topic I deal with concerns many families with small children who have emigrated from the Hungarian-speaking area. The second half of the event is always interactive: I answer the questions of the participants, which is how the parents also exchange their thoughts and share their experiences. It is a special experience for me that the organizers always arrange my accommodation with families. It is interesting to see how others experience living abroad, integration and habits that are different from their home country’.

Do you also work in Switzerland? Do you receive any invitations here?

RCS: Yes, at first, I held workshops mainly in municipal cultural centres. It was interesting when the cantonal adult education institute showed up for a “quality assurance check” for the first time: they attended the event and listened carefully. And because I fortunately “passed my test”, they have been providing free advertising in their brochure for me. Recently, kindergartens and schools in the Zurich area are asking me for support, as they also have a large number of children raised in bilingual or multilingual families. In Switzerland, local networking is very important, which, perhaps needless to say, is not a given for me as a foreigner. In addition, education is mainly dominated by local people.

‘How did the Covid 19 situation affect your activity? Were you able to switch to online education and counselling?’

RCS: In counselling, this transition has been smooth, but it proved less useful for other events. For example, in the case of EU-funded Erasmus+ teacher training, this is currently not legally possible. In addition to professional training, an important goal of these one-week trainings is for teachers to travel abroad, gain experience, practice the use of a foreign language, and establish personal working relationships with colleagues from other countries. The online space is less suited to creating the kind of interaction that goes without saying in a personal presence. I assume that changes in regulation are to be expected in the future.

In what language do you hold these trainings?

RCS: I have three working languages: Hungarian, German and English. This is undoubtedly a big challenge! In English and German, I have to “educate” all those who often have English or German as their mother tongue on a “quasi” native level. It’s quite a tiring task to do, however – if the research results can be believed – then this continuous brain training will significantly slow down the aging of my brain J.

How much can we see in your book about your own family stories?

RCS: Of course, I couldn’t resist smuggling some family stories into my books: with four children, I went through a lot. At the same time, I brought examples from dozens of families from different life situations and countries – from parents, grandparents and from the young people themselves.

You mentioned that you came into contact with languages at a young age. How did that happen?

RCS: Yes, my dad enrolled me in a German class when I was five years old. This was not at all common in the Hungarian county-side in the 1970s, as the practice of early language development had not yet been invented. Since there was no preschool group, I could only get into a school group – without being able to read and write. However, I was only accepted on the condition that I learn all the reading material by heart, so that when the others read them aloud, I could also get involved in the task. The experiment continued as my dad found a family in Germany, where I could stay for a language vacation. At the age of six, I was riding a small Trabant to Dresden (former GDR) with the German family. I spent three weeks in a full-German environment without a single word in Hungarian. Of course, without parents, a mobile phone or a safety net…

How finally do you feel about settling in Switzerland? Would you stay in Switzerland in the long term or do you want to live elsewhere? Maybe in Vienna again?

RCS: I have no idea what the future holds. The situation created by the coronavirus showed me how unpredictable our lives were and how quickly our plans could be shattered.

About the author:

Beatrix studied architecture and urban design in Budapest. Today she lives and works in Switzerland where she founded an online art gallery, ARTODU, to support emerging Hungarian artists. In 2018 she started publishing her short stories online, mainly for her friends, both in English and Hungarian. She writes in her two blogs ARTODU ART BLOG and BEATRIX KOCH BOOKS about art, culture and interesting stories. In 2019 she started to study creative writing at the Peterfy Academy.

Credit photo Ahoy