Finance Column Rosa Sangiorgio

Chapter 11: Picking your Bonds – Investing made easy by Rosa Sangiorgio

Investing made easy is a bi-weekly series by Rosa Sangiorgio exclusively for Vivamost

A bond is a loan that you, the investor, make to the bond issuer. If investing means supporting those projects that you believe will contribute to the future of the world that you envision, this is valid whether you participate in the long-term capital of a company (through equities), or “lend” them money, buying bonds.

Governments, corporations and international organizations issue bonds when they need capital. If you buy a government bond, you are lending that government money. If you buy a corporate bond, you are lending that corporation money.

Photo by Roman Synkevych on Unsplash

There are a number of key variables that characterize the risk profile of a bond: its price, interest rate, yield, maturity, credit ratings. Together, these factors, as well as others, determine whether it might be an appropriate investment for you.

Issuer risk: can the borrower pay back its bonds?

If you believe a company can’t pay back its bonds, you probably don’t want to lend them your money. So, how do you estimate whether the borrower is able to meet its debt obligations?

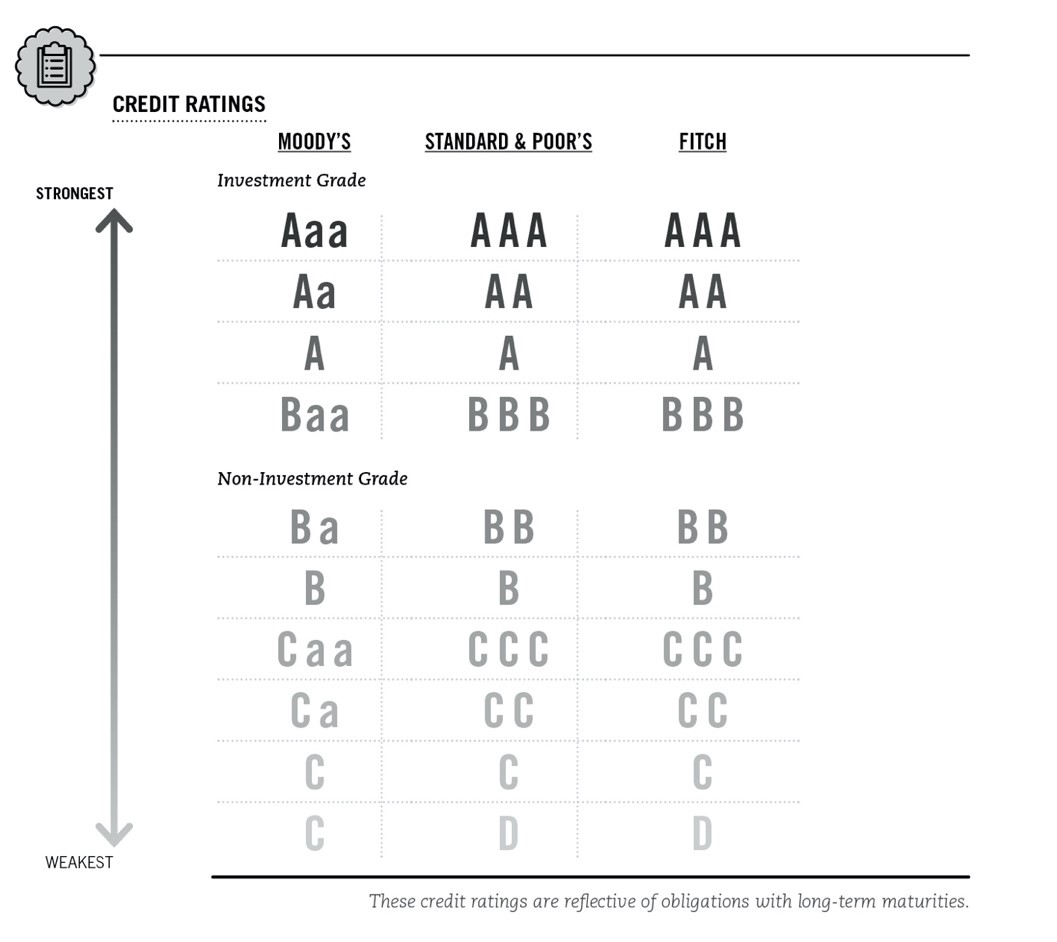

You may have heard of Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch? They estimate creditworthiness by analyzing the issuer’s financial condition. The higher the rating (AAA is the highest, and it goes down from there, like school grades) the greater the likelihood a company will honour its obligations and consequently, the lower the interest rates it will have to pay. Investors who purchase bonds with low credit ratings can potentially earn higher returns, but they must bear the additional risk of the bond issuer defaulting.

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

Bear in mind that ratings are opinions, and you should understand the context and rationale for each opinion. Never rely solely on credit ratings as a measure of credit risk but use a variety of resources to assist in decision making.

When a bond issuer fails to pay back (either interest or principal at maturity), it “defaults”. Defaults can also occur when the issuer faces bankruptcy; in this case, as a bond is a type of debt obligation, bondholders (as creditors of the bond issuer) will have priority rights over equity holders.

Government bonds (or “govies”): in general bonds issued by the government or by local municipalities are considered among the safest, consequently, the interest rate is very low. They’re considered so safe that investors often refer to the government’s interest rate as the “risk-free rate.” Clearly lower-rated governments (e.g. developing countries) will pay higher coupons than high rating ones (e.g. Switzerland).

Photo by Jonas Zürcher on Unsplash

Corporate Bonds are issued by companies:

- Investment-grade bonds are issued by companies with good credit ratings. Because they’re safer borrowers, they’ll pay lower interest rates than poorly rated bonds but typically more than the respective government pays.

- High-yield bonds offer a larger payout than typical investment-grade bonds, due to their perceived riskiness.

Photo by Austin Distel on Unsplash

Interest rates and maturities

Like a loan, usually, a bond pays interest periodically and repays the principal at a defined time, known as maturity.

The interest paid can be fixed, floating or payable at maturity.

- Fixed-rate bonds pay an interest rate that is established when the bonds are issued.

- Some issuers, however, prefer to issue floating-rate bonds: the rate is reset periodically in line with the then prevailing interest rates.

- The third type of bond does not make periodic interest payments. Instead, the investor receives one payment at maturity. Known as zero-coupon bonds, they are usually sold by the issuer at a substantial discount from their face amount, so basically both interests and capital are paid together at maturity.

To simplify things we’ll talk mostly about fixed-rate bonds in the next paragraphs.

Suppose a company wants to install solar panels on their manufacturing plant. To pay the cost of CHF 1 million, the company decides to issue a bond. The company (now referred to as the bond issuer) determines an annual interest rate, known as the coupon, and a time frame within which it will repay the principal (the CHF 1 million). To determine the coupon, the issuer takes into account the prevailing interest rate environment to ensure that the coupon is competitive with coupons on comparable bonds and is attractive to investors. For example, they decide to issue five-year bonds with an annual coupon of 5%. At the end of five years, the bond reaches maturity and the corporation will repay the face value (the CHF 1 million).

Photo by Biel Morro on Unsplash

How long it takes for a bond to reach maturity, plays an important role in the amount of risk and the potential return an investor can expect. A bond repaid in five years is typically less risky than the same bond repaid over 30 years because many more factors can have a negative impact on the issuer’s ability to pay bondholders over a 30-year period relative to a 5-year period. In other words, an issuer will have to pay a higher interest rate for a longer-term bond. The investor, on the other side, earns greater returns on longer-term bonds, but in exchange for that return, incurs additional risk.

How bond price and yields move?

Newly issued bonds normally trade at or “close to par” (100% of the face value). Bonds traded in the secondary market fluctuate in price, in response to changing factors such as interest rates, credit quality, general economic conditions and supply and demand.

The yield is the return earned on a bond, based on the price and the interest payment received. You usually hear about current yield and yield to maturity (YTM). The current yield is the annual return on the amount paid for the bond. The YTM is the total return received by holding the bond until it matures (and is typically quoted as an annual rate). The YTM enables you to compare bonds with different interest rates, or coupons. Be sure you know the YTM of any bond you are considering to purchase!

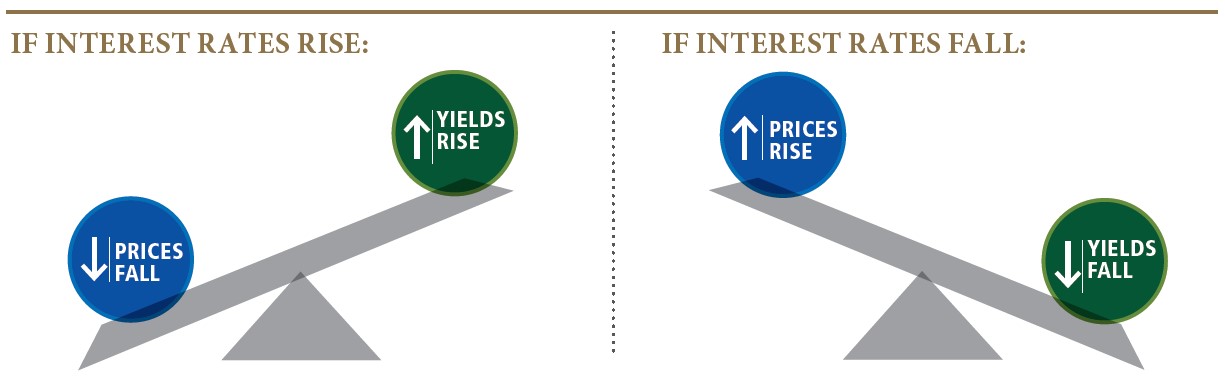

Courtesy: Rosa Sangiorgio

Generally, bond prices and interest rates tend to move in opposite directions. When interest rates are rising, new bonds will pay investors higher interest rates than old ones, so old bonds tend to drop in price. Falling interest rates, however, mean that older bonds are paying higher interest rates than new bonds, and therefore, older bonds tend to sell “at a premium” in the market.

When the economy accelerates, central banks may raise interest rates in order to slow down growth and prevent inflation; such an increase in interest rates will reduce bond prices. When the economy slows down, interest rates fall, lifting bond prices. Investors may try to predict whether rates will go higher or lower, but trying to time the market is never a good idea for non-professional investors, you’ll end up losing time and money.

Not all bonds are created equal: bond diversification

Regardless of your investment objectives, diversification is an important consideration in building any portfolio. A good bond allocation might want to:

- diversify the portfolio by the issuer, thus reducing issuer risk

- stagger the maturities to reduce interest-rate risk otherwise known as “laddering”

- manage the overall duration of the portfolio to ensure right positioning to interest rates expectation, and to your own objective

Additionally, you can decide to buy and hold to maturity (just reinvesting your coupons periodically), or to actively manage your portfolio (therefore needing to have an opinion on the economy, the direction of interest rates and/or the credit environment).

Photo by John Barkiple on Unsplash

I hear you. Investing in individual bonds is a challenge. In addition to the wide range of moving parts inherent in each bond we have mentioned in this article, the bond market can also be difficult to access in terms of information and liquidity.

If individual bonds seem too complex and you don’t want to consult a financial advisor for guidance, you can explore bond mutual funds and bond ETFs that provide diversified exposure even if you can’t invest large amounts.

We’ll explore the world of Mutual Funds and ETFs in the next chapter.

About the Author:

Rosa Sangiorgio, an Independent Advisor, is an expert at scaling investment methods that generate positive, socially responsible and environmental welfare impact in addition to a financial return. She worked for several European Financial institutions in the area of Wealth Management and Private Banking. Also, she was Head of Sustainability and Impact Investing in the Investment Management team of Credit Suisse until January 2020. Rosa is also a CEFA charterholder and TEDx speaker.